[Warning: Contains material discussing poetry and the nuances of poetry that may be disturbing (i.e. boring) for a general audience.

Probably not for the entrenched Metrophobe (one who fears poetry) and not for those who suffer from oimoiokatalichiphobia (the fear of rhymes)…. though if you have omphalophobia (fear of navels) you’ll probably be fine. Contemplate yours as you wish.

This post contains significant discussion of how to best read poetry that might drive ordinary people (i.e. non-poetry-minded folks who don’t live in their own heads) mad. In other words, run for the hills because Anneliese and Pernoste are talking about poetry.]

So, what exactly is a poem? Most of us who write poetry, perhaps don’t truly know (though I won’t include you in my professed ignorance). Certainly, Pernoste and I picked it up on the streets along with a number of bad habits, so many of the nuances were not apparent to us that, only in the past few years, we are starting to appreciate.

Kind of like with wine and art… in poetry, we know what we like and what we don’t like, but we haven’t always been able to say why.

[Pernoste: haha, “learned on the streets.” I have images in my mind of a bunch of tough kids wandering the streets causing trouble and spouting poetry.]

Haha. I know that Pernoste and I tend to think in terms of whether a poem is creative, whether the words flow smoothly, and if it doesn’t feel contrived or forced. So I confess (cringing as I do so because I hate to generalize even my own biases) that I often do not fully appreciate rhyming poetry.

There, I said it.

Yet, I have read amazing rhyming poetry at times that is done so well with rhymes so smoothly done that you hardly notice them. And there are others where I feel the rhyme intensely and musically, and it fits so perfectly and amazingly.

So I wanted to talk a little about rhyme and rhythm and poetry to help those who struggle to write poetry. Rhyming poetry too often feels forced on me, which makes me not like it so much. Maybe free verse would be good for those of you who are rhyme-challenged.

[ Pernoste: I’m pretty sure I don’t know this woman. I love ALL poetry.]

Don’t listen to him. He said the very same thing to me many times about rhyming poetry. We sink or swim together, partner.

But, actually, we’re going to sing the praises of rhyming poetry if you bear with us. Pernoste cannot carry a tune for praise-singing. Sorry, but you can’t, Pernoste. But I sing beautifully.

[ Pernoste: my ears are bleeding already… but proceed, Anneliese. Just kidding, you do sing beautifully.]

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — -֎ — — — — — — — — — — — — — — -

So let’s start at the feet and work our way up. Bear with me. It will be fun. At least for us, haha. Run away if you must… while you can.

[Pernoste: There they go. Wow, they’re fast!]

Poems have different levels of rhythm and rhyme, and even the free verse poems, without rhythm and rhyme, often have some sort of structure.

Sometimes, those darn clever poets have strategies of structure and rhythm and rhyme that take study just to figure out how they’re manipulating how we read and understand their work. I’ll explain later with an example by Lord Byron.

Starting with feet… the “foot” is the basic measure of the accentual-syllabic meter.

[ Pernoste: OMG, what the heck does that mean? Is that even English?]

It just means that the foot is the smallest building block of the poetic structure.

And the meter just refers to how many “feet” are used per line.

So you’ve heard of iambic pentameter, most likely, which just means that there are 5 “iambs” strung together into each line.

This isn’t all of them, but some feet aren’t worth discussing right now.

[ Pernoste: mine certainly aren’t.]

iamb: a metrical foot containing two syllables with the first syllable “unstressed” and the second syllable stressed. Example: Today (to DAY).

trochee: a metrical foot with two syllables in which the first is stressed and the second unstressed. Example: Wander (WAN der)

anapest: a metrical foot with three syllables, the first two unstressed and the last stressed. Example: Unaware (un a WARE)

dactyl: a metrical foot with three syllables, the first one stressed and the last two unstressed. Example: Yesterday (YES ter day)

amphibrach: one unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable and ending with another unstressed syllable. Example: (me DUS a)

amphimacer: one stressed syllable followed by an unstressed syllable and ending with another stressed syllable. Example: (GIVE me FOOD)

FYI, Shakespeare used mostly iambic pentameter, Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” is in trochaic tetrameter, and Homer’s “Iliad” is in dactylic hexameter.

[Pernoste: My father told me I was born with dactyllic feet, so that’s why I could swim so fast… especially when I’m not drowning.]

TMI, Pernoste. Anyway… why is this kind of poetry structure even useful? Well, poetry has somewhat evolved away from much of this rigidity, however having a structured rhythm to a poem can make it flow better and add a musical/magical quality, making it easier to remember.

Iambic and trochaic tend to add a light, lilting quality to the words, whereas dactyl and anapest add the potential to capture more drama.

A simple illustration of the impact of feet:

(1) My father said I should go to the house.

my FATHer SAID i should GO to the HOUSE (iamb-iamb-anapest-anapest -the emphasis when you speak the line is mostly on GO) [Note: could also be read awkwardly as iamic pentameter — my FATHer SAID i SHOULD go TO the HOUSE, but it seems too strange to me.]

(2) My father sent me to the house.

my FATHer SENT me TO the HOUSE (iambic tetrameter — emphasis on SENT)

Read these aloud. Both can be read naturally, and conversationally. But how you structure the feet can dictate what words you emphasize.

In the first case, it is more dramatic and less melodic/rhythmic but focuses on GO. So if it were a message of urgency, this uneven rhythm would work well in substituting RUN for GO.

The second example is more rhythmic yet puts less energy/urgency into going to the house.

— — — — — — — — — — — — — -֎ — — — — — — — — —— — — — — — -

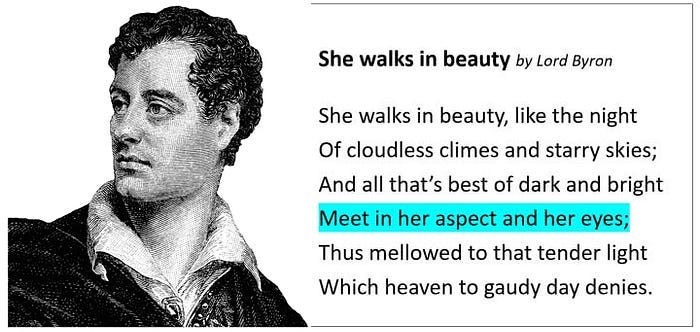

Now for a terrific example of a master poet. Isn’t “She walks in beauty” a beautiful rhyming poem by Lord Byron (in iambic tetrameter, with a rhyme scheme of ABABAB)??

[ Pernoste: yes, this is a great one. One of my favorites, and not just because he’s older than me].

[ Anneliese: he’s dead, Pernoste.]

[ Pernoste: I guess that’s why he doesn’t write anymore.]

Anyway… Byron’s poem flows lightly, and the rhymes feel natural within the flow. No surprises in structure or rhythm, except for line 4 (highlighted in blue) which can be read in two ways.

1. awkwardly in iambic tetrameter as: “meet IN her ASPect AND her EYES “

— forces an emphasis on “ IN and AND“

2. more rhythmically (and natural to read aloud) as an irregular dactyl-trochee-amphimacer): Depends on whether you naturally emphasize the AND as well. “ MEET in her ASPect AND her EYES “.

—major emphasis on “ ASPect” and “ EYES “

Which did he intend? As he was a master of the craft, I can’t imagine he would have put an awkward line of iambic tetrameter in there.

Just beautiful the way he played with rhythm to highlight this line as the only line with the first syllable emphasized.

[ Pernoste: Apparently she had a nice ASpect.]

[ Anneliese: I see what you did there, haha.]

— — — — — — — —— — — — — -֎ — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — -

OK, JUST ONE MORE EXAMPLE OF A LOVELY RHYMING POEM…….

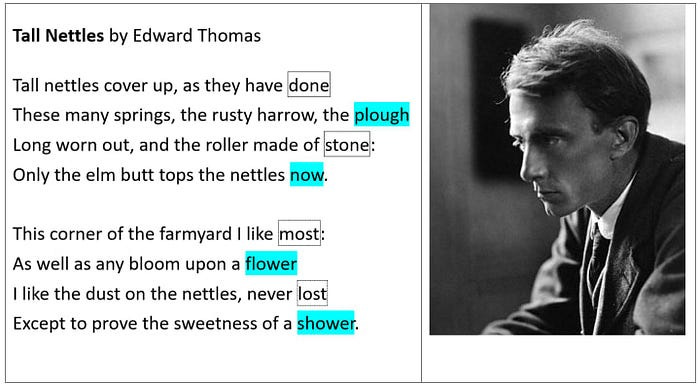

Just want to share one more poem, by Edward Thomas, who started writing poetry at 37 and died a few years later in WWI.

This poem has an eclectic structure I won’t even try to explain, but it forces me to read in such a lovely way with smooth and seamless starts and stops.

There are amazing subtleties in his poetry, including the addition of “sight rhymes” alternating with “perfect rhymes”.

[A sight rhyme is two words that look like they should rhyme, but they don’t (done/stone, most/lost).

The perfect rhymes, of course, are plough/now and flower/shower. The sight rhymes only create an additional order to the poem, and some amazement on my part. It’s hard enough to rhyme smoothly, but to also add sight rhymes…. wow.

Another notable thing is that lines 4 and 8 differ from the others in that they are not directly descriptive like the other lines, rather these 2 lines are metaphorically descriptive.

Line 4 describes the height of the nettles only by describing that the elm butt barely tops them now.

Line 8 implies the washing of the dust from the nettles by the rains in a beautiful way.

You can also say that the first three lines are dispassionately descriptive, whereas lines 5,6,7 are sentimental and speak of feelings.

Really brilliantly written, organized, emoted, structured, everything, all packed into an 8-line lyric poem. Pretty sure he was some sort of poetry genius.

— — — — — — — —— —— — — — — -֎ — — — — — —— —— — — — — — -

Rhyme Schemes

OK now it’s time to talk, briefly, about rhyme schemes, but we’ll save talking about all the definitions of rhymes [perfect rhymes, imperfect rhymes, slant rhymes, pararhymes, forced rhymes, semirhymes, eye rhymes, etc… ] for another time.

[ Pernoste: Thank you. Some of those drive me nuts. I like the slant rhymes, though.]

Poets use rhyme schemes for a variety of reasons, partly to make something beautiful, partly for tradition, and perhaps partly for the challenge of writing something amazing with such strict rules.

Of course, the fact that rhymes repeat at regular intervals really increases the rhythm, and it makes a well-crafted rhyming poem pleasant to listen to and generally more memorable.

Types of typical poetry

Alternate rhyme: ABAB CDCD EFEF

Coupled rhyme: AABBCC

Monorhyme: AAAA

Chain rhyme: AABA BBCB CCDC

Italian sonnet: ABBA ABBA CDECDE

Shakespearean sonnet ABAB CDCD EFEF GG

Ballad: ABABBCBC ABABBCBC ABABBCBC BCBC (underlined C is same word)

Concrete poem: structure due to pattern of words on the page

Free verse: no rhyming structure

Haiku: unrhymed poetic form consisting of 17 syllables arranged in three lines of 5, 7, and 5 syllables, respectively

We were going to give some examples of these, but we decided to do something a little different……

— — — — — — — — — — — — -֎ — — — — — — —— — — — — — — — — -

WELCOME TO THE MULTIVERSE OF POETRY

OK, so here was the challenge Pernoste and I placed for ourselves to try in our humble way to illustrate the range of different feelings you can generate in different forms of poetry… just a little sampling from the multiverse of poetry. We decided to write essentially the same lyric poem, conceptually, in:

1. free verse

2. Shakespearean sonnet

3. Concrete poem (just cuz it’s fun)

4. haiku

[ Pernoste: she made me do this with her.]

[ Anneliese: I did not, you liar with pants on fire. It was your idea.]

FREE VERSE:

Here it is. Right off the top of our heads, starting as a stream of consciousness with the two of us and eventually shaping up into a free verse poem that we felt had some potential as a sonnet.

We gave ourselves 30 minutes to write this, and we’re pretty happy with it.

Born Today

Can you see that I was born just today,

finding myself in the mirror, eyes changed?

It started there first, then moved to my smile

and wriggled right into my hopes and dreams.

If I want to fly, I’m sure I’ll find wings.

If I try to sing, my voice will seek its freedom

in sweet lyric tones, soulful and bright

to bring you away to see things differently.

No, you cannot break this from me now,

not with deaf complaints you cannot voice,

not with mute requests that see nothing

while you’re still asleep in your cocoon.

I am happy for you, as I’m happy for me,

for tomorrow, tomorrow, it may be you.

SHAKESPEAREAN SONNET:

Translating the free verse to a sonnet was a little painful. Kind of like squeezing my size seven foot into a size three shoe.

[ Pernoste: for me more like pulling my brain out through my ear. I haven’t written a sonnet in a while.]

We tried to capture most of the elements of the free verse while also adhering to iambic pentameter and trying to choose smooth rhymes that flowed well in the poem.

Born Today

Who will believe that I was born today

seen lit in eyes so bright in mirror’s shine

while to my smile it quickly found its way

into the heights of hopes and dreams of mine.

I would make wings if I should want to fly,

and if my voice could find itself made free

to sing in sweetest tones, with soul, I’ll try

to bring you from yourself so you can see.

To break all this from me you will not do,

with ever deaf complaints you cannot voice

with mute requests that bring nothing to view

as your cocoon holds you asleep by choice.

I’m glad for me, and also glad for you,

for you could be born new tomorrow, too.

CONCRETE VERSE:

Doing concrete verses makes me feel like a kid. \

[ Pernoste: yeah we had some fun with this.]

It’s about using the poem and physically reshaping it and using the space on the page to express other aspects of the poem.

So here, the joyous lines are breaking free, whereas the middle distracting lines (dealing with an unseen other) are rigid and constricted. Then at the bottom two lines, there is freedom and joy again. Ultimately it forms a joyous tree of sorts.

HAIKU:

This may be my first haiku. I just have too much to say to squeeze into three lines.

Pernoste: (silence)

Obviously we had to trim down our free verse concept, just a tad. And we had to pare it down to three general concepts within the structure of syllables and lines.

[Pernoste: I like the enigma of the last line. Could be interpreted in a couple of ways.]

Born Today

I was born today

finding my lost hopes and dreams.

Maybe you, tomorrow…

OK. So that was a fun exercise. Feedback, positive or negative, or humorous or weird…will all be good.

[ Pernoste: I’m kind of in the mood for weird, but yeah.]

Hope you enjoyed our latest little foray into the world of poetry. And I think we both have much more appreciation of rhyming poetry now.

[ Pernoste: I have always loved ALL poetry. Who are you?]

Haha, well, rhyming and rhythm are not so scary, is it? Maybe the next topic will be.

Love,

Anneliese & Pernoste

Check out our other writing here on Substack and Medium and Instagram and Youtube.

Revised from an essay originally published at https://vocal.media